Oakland and Sacramento city attorneys: Civilian oversight is crucial to policing

Brian Lee-Mounger Hendershot is the managing editor for Western City magazine; he can be reached at bhendershot@calcities.org.

For over a decade, California voters have demonstrated a clear preference for police reform — often in response to sustained, high-profile cases of police brutality and misconduct. One way that cities can address these concerns is through civilian oversight organizations. Although these entities date back to at least 1931, it’s only recently that they have become particularly prevalent.

What exactly civilian oversight looks like varies from city to city. For some, civilian oversight puts the power to police the police in the hands of the people. For others, civilian oversight is a way to reform and enhance policing policies and practices.

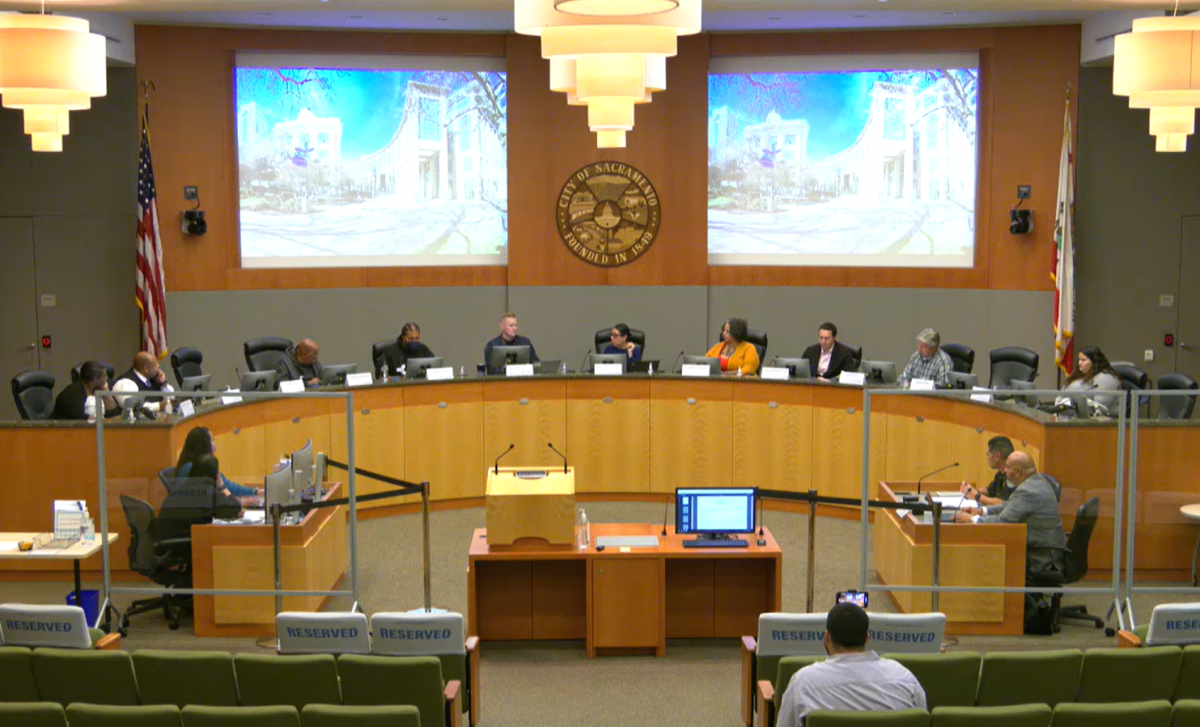

Western City sat down with city attorneys from Oakland and Sacramento to discuss their cities’ very different approaches to police oversight. Oakland — which is currently under a federal monitoring degree — has a complex system of checks and balances that requires voter approval to change. Sacramento also has a multi-pronged oversight system but with fewer powers. And unlike its counterpart in Oakland, the city council can dissolve the civilian review commission.

Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Brian Hendershot, Western City: Why is civilian police oversight important?

Ryan Richardson, Oakland: What I tell people is think about the friends you have at your workplace. And then imagine a situation where one of you was assigned to be the investigator of the rest of that group. When I talked to people about it that way, they realized that it wouldn’t work. You either wouldn’t be able to do your job because you’d have a conflict of interest, or you would do it well and you would be ostracized from the group. And that’s essentially what it comes down to in police departments.

That, in a nutshell, is why you need civilian oversight. You need somebody from the outside of what otherwise tends to be a pretty tight-knit group to lay eyes on these issues.

Audreyell Anderson-White, Sacramento: Civilian oversight creates an opportunity for the community to have a working relationship with the police on policing policies — where they can get greater involvement with the development of the practices for policing. It allows people with different backgrounds and socioeconomic experiences to articulate the impact of policing on their particular community, hear about policing practices and policies, and engage in the development of those policies in one venue. It is a very communal approach to policing.

BH: Tell me a little bit about how these structures came to be in your communities.

RR, Oakland: The civilian Police Commission is at the head of our structure. The Police Commission itself is looking at policies at the very highest level. They’re helping the Oakland Police Department (OPD) fashion its policies and they’re making high-level decisions like helping decide who the chief of police is going to be.

Under the Police Commission are two subsidiary offices. The Community Police Review agency investigates allegations that individual officers engaged in misconduct. And then in 2020, with the passage of Measure S1, we also established an Office of Inspector General — it’s the auditing arm of the Police Commission. They’re investigating how the system is working and making recommendations for how the city, the Police Commission, and the Police Department can improve.

To my knowledge, it is one of the strongest civilian oversight structures in California because of how comprehensive it is and how many powers voters of Oakland have entrusted to those three bodies.

AW, Sacramento: The Police Community Review Commission developed over time. In 2004, the city council created a formal advisory commission to report on then-current policing practices and advise on bias-free policing. It served between the years 2005 and 2015.

Since then — as with the rest of the nation — issues of trust and police accountability have become increasingly important for the city. And in 2016, the city council created the commission but increased its scope from bias-free policing to [cover] all police policies and practices and provide a venue for community engagement. The commission is an advisory body of the city council, separate from the Police Department and Office of Public Safety Accountability.

Note: The Sacramento Office of Public Safety Accountability (OPSA), established in 1999, reviews, audits, and investigates police policies, complaints, incidents, and practices.

BH: OPD has been under federal oversight for nearly two decades. Federal attorneys provide reform recommendations and monitor OPD’s progress. How does Oakland’s relatively new oversight system work with the federal oversight system?

RR, Oakland: The intent is for our Police Commission, our Inspector General in particular, and our Community Police Review Agency to replace the structure that we have in place now. We’re not going to be under monitoring forever. There are a lot of really bright people in the city who are working tirelessly to get the city out of federal oversight. And we’ve also been looking ahead so that when that happens we have structures in place to replace the support that the federal monitoring team has been providing for the last several decades.

The federal monitor has traditionally helped OPD shape and amend its policies. That’s where the Police Commission is stepping in. The monitoring team has helped OPD audit itself and improve its systems, and then root out issues and give recommendations on how to fix them. That’s where our Inspector General fits in.

The other thing that the city is striving toward is actually doing away with the internal affairs division of OPD, such that all investigations will be handled exclusively by the Community Police Review Agency. Then the dozen or so sergeants that currently do those investigations will be back on the street, investigating crimes and supervising squads.

BH: Audreyell, what powers does the Sacramento Police Review Commission have?

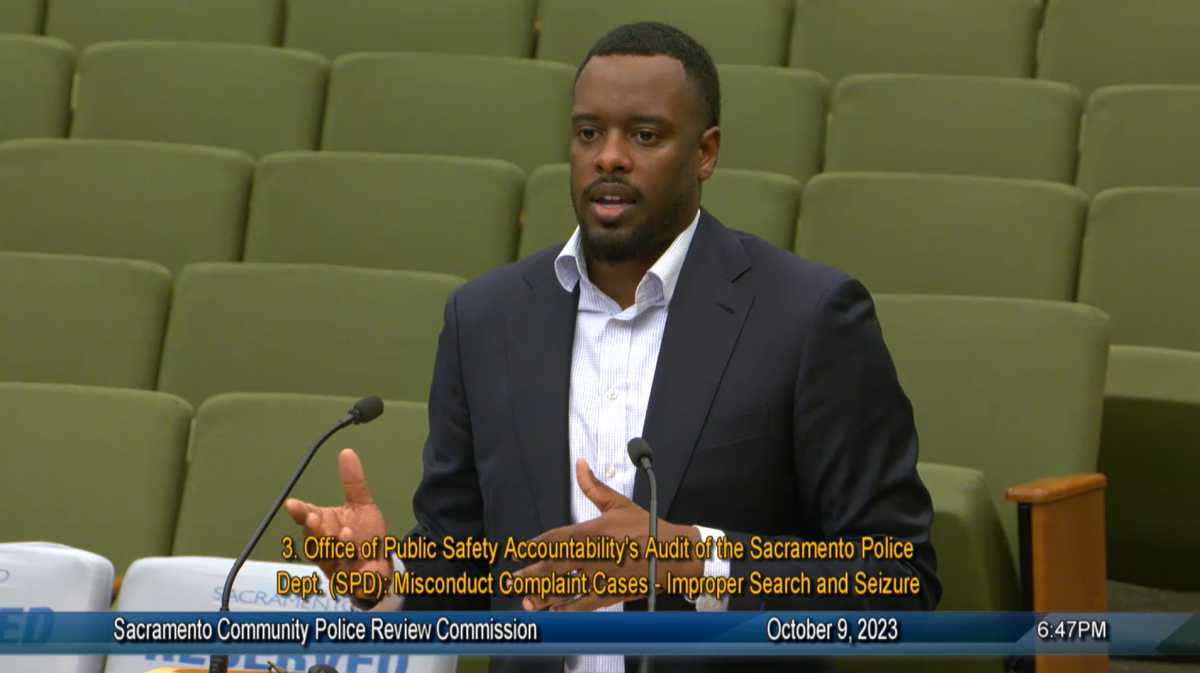

AW, Sacramento: The commission is empowered to advise the mayor and council on police practices, policies, and best practices. They also work with OPSA by reviewing quarterly reports on different topics. For example, the commission recently reviewed OPSA’s report on search and seizure. They’re empowered to review reports on complaints against Police Department personnel and whether there’s a pattern of misconduct for policing policies.

The commission reviews these reports, asks questions, provides input, and makes recommendations to the mayor and council to improve police policies and practices. It helps educate the commission, as well as share what they’re hearing from the community with OPSA. The commission is also empowered to go into the community and inform the community of upcoming policing policies or changes. People can consult the council and share their own thoughts. Or they can talk to this commission and the commission can relay the information to the city council.

BH: Whenever there’s a big change at any organization, there’s going to be some level of resistance. How have your cities responded to pushback against this new type of oversight?

RR, Oakland: There have been bumps in the road and growing pains over the years. It is such a departure from what existed before, where decisions were just being made by the police chief and the deputy chiefs. But I think what I’ve seen over the years is constant improvement. And the Police Commission and our Community Police Review Agency are getting more and more functional over time.

Culturally, it’s starting to just become part of the norm. It’s not a new thing anymore. This is part of policing in Oakland; this is part of police oversight in Oakland. I think when implementing something like this, there’s no substitute for time. Any jurisdiction that implements something like this — if it really has teeth — and their civilian oversight really has power and responsibility, there is going to be a period of acclamation.

And I want to be clear, there are people at OPD and the city who have always embraced transparency. But in any organization with hundreds of people, you’re going to have people who don’t. Some have gone through what I think of as the stages of grief, where it starts with denial and eventually, they get to acceptance.

And there’s been another development in California that’s kind of gone along coincidentally with our civilian oversight. And that’s the introduction of SB 1421 and SB 16. Those were watershed pieces of legislation at the state level that finally started to peel back the veil of confidentiality around police personnel records and police discipline records.

AW, Sacramento: I would agree with Ryan. I would say too, our electeds really stepped up to highlight the importance of the commission and even put together special meetings to make sure not only the commission, but the entire city understands the importance of this effort. The mayor, former council members, and the current ones are calling attention to it and highlighting that this [inequity] needs to be addressed and this is something that the city needs to direct its resources towards.

Sacramento has had personnel changes as well — not just in the Police Department, but the Commission and the Office of Public Safety.

BH: One of the things I hear fairly consistently when talking to city leaders about public safety is the need to improve community trust. How do these oversight efforts fit into the more day-to-day efforts to increase public trust?

RR, Oakland: It starts with sunshine, accessibility, and transparency. There’s not a police department in the country, really in the world, that doesn’t have its issues. But when police departments have their issues, the stakes are much higher because they are entrusted with an immense amount of power. They are carrying deadly weapons on our streets. They are sworn to protect residents and use force if necessary. So that really sets them apart.

Transparency is the foundation for building trust. I think that’s true for government across the board and police departments are no exception. The residents need to have trust that they have a window into what’s happening at their police department — good or bad. And then from there, you can work on improving the department.

AW, Sacramento: Public safety is a critical responsibility and there’s a negative history and experience out there from which people view public safety. Civilian oversight allows community members to have an “intermediary” to engage in informal and formal collaboration with police departments and city leadership from the community’s lenses.

Here in Sacramento, for example, we have a youth commissioner on the commission. It gives voice to different socioeconomic, ethnic, and generational backgrounds in a way you wouldn’t get otherwise. Sacramento’s requirement that commission members not be past or present peace officers or current city employees is so important because it helps the community feel like there’s representation of their concerns, outside of city staff, [and so they can] really be heard.

BH: What do you think is the future of civilian police oversight agencies?

RR, Oakland: I think they will become more common. And this kind of ties back to one of your first questions. Again, it’s not unique to police departments. When there are allegations of misconduct, when there are issues of accountability, the investigation has to come from outside of the group where the potential issue exists. I think that increasingly, there’s going to be recognition that we must have oversight from outside of the police departments.

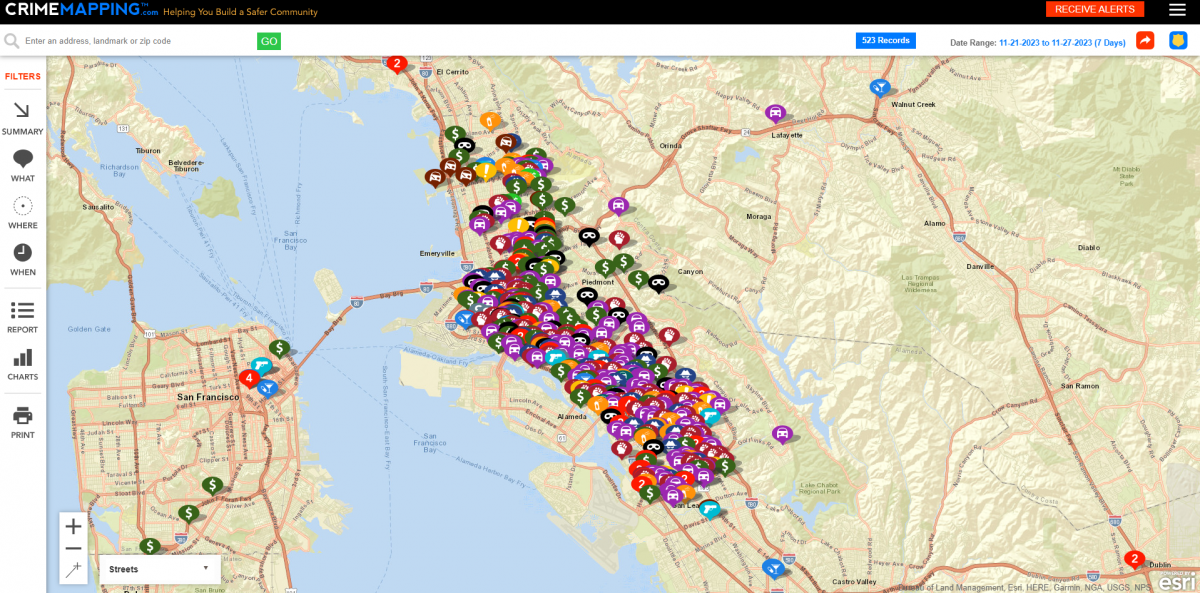

It starts with transparency. Even if you don’t have a police commission or community police review agency, you can start requiring the publication of data by your police departments.

Adopting body-worn cameras is another way of creating records that the public can see in order to promote transparency. But once you have the body-worn cameras, have meaningful and earnest policies that give the public timely access to footage. There are things that agencies can do immediately to be more transparent, even if they don’t have a civilian oversight structure in place yet.

AW, Sacramento: I agree. I think civilian oversight will become a natural and integral part of developing policing policies as more and more [people] see the communal benefit of partnering, creating a safer community, opportunity for community member investment, and opportunity for officials to listen and collaborate to address community needs and concerns.

BH: Is there anything else you want to say about civilian oversight?

RR, Oakland: Leaders need to be prepared to invest in civilian oversight. Having a board or commission of volunteers that engages in oversight is a good thing. But there really needs to be paid, professional staff supporting those efforts and working on it day in and day out. It’s complicated. It’s time-consuming, and it’s ever-changing. And so, I would say if a local government agency is really serious about it, they need to invest in it financially.

AW, Sacramento: It’s imperative. For officials or communities that are interested in civilian oversight in their communities, I think the first step is putting real action behind words. When there’s a will there’s a way, right?